- Qcecuring Editorial Team

- 21 Dec, 2025

- 17 Mins read

- Security Encryption Cloud

Introduction

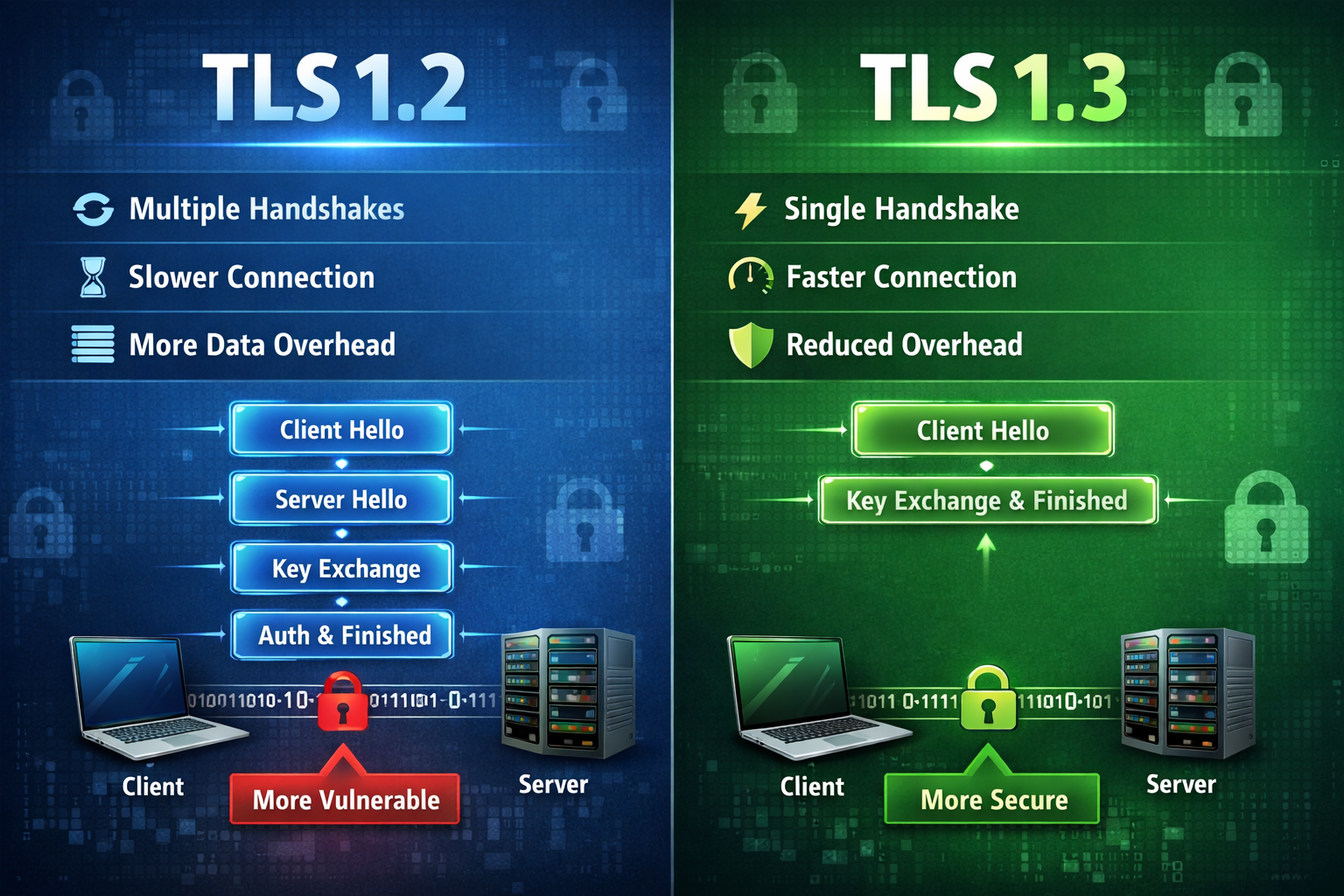

The web demands speed without compromising security. For over a decade, TLS 1.2 served as the backbone of encrypted internet communications, protecting everything from banking transactions to healthcare data. But technology evolves, and so do threats.

In August 2018, the Internet Engineering Task Force finalized TLS 1.3 after years of development and rigorous cryptographic analysis. The result isn’t just an incremental update, it’s a fundamental reimagining of how encrypted connections should work in cloud-native, zero-trust environments.

TLS 1.3 delivers measurable performance improvements while simultaneously strengthening security guarantees. Connection establishment is 50% faster. Weak cryptographic algorithms are gone. Forward secrecy is mandatory, not optional. For enterprises navigating digital transformation, understanding these differences isn’t optional—it’s strategic.

What This Guide Covers

This comprehensive analysis explores the technical and operational differences between TLS 1.2 and TLS 1.3, providing enterprise security teams with actionable intelligence:

- Core architectural changes that drive performance improvements

- Security enhancements and eliminated vulnerabilities

- Handshake process optimization from 2-RTT to 1-RTT

- Cipher suite simplification and mandatory forward secrecy

- 0-RTT session resumption capabilities and replay considerations

- Enterprise migration strategies with minimal disruption

- Cloud-native deployment patterns for service meshes and API gateways

- Compliance requirements from NIST, PCI DSS, and industry standards

- Real-world use cases including mTLS, IoT, and Zero Trust architectures

What Is TLS and Why Protocol Versions Matter

Transport Layer Security is the cryptographic protocol that encrypts data traveling between clients and servers across the internet. Every HTTPS connection, API call, and secure email transmission relies on TLS to provide three fundamental guarantees: confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity.

TLS evolved from Secure Sockets Layer, inheriting the mission of protecting data in transit while addressing the security vulnerabilities that plagued earlier protocols. But unlike application software that can be patched frequently, cryptographic protocols require careful, deliberate evolution. Each version must maintain backward compatibility considerations while addressing newly discovered vulnerabilities.

Protocol versions matter because security isn’t static. What seemed cryptographically sound in 2008 may prove vulnerable in 2025. The cipher suites and key exchange mechanisms that powered TLS 1.2 included algorithms that researchers later compromised. Some provided weak security guarantees. Others enabled downgrade attacks where adversaries forced connections to use weaker encryption.

TLS 1.3 takes a different approach, eliminating problematic features entirely rather than trying to patch them. This philosophy shift makes the protocol inherently more secure by reducing the attack surface and removing the complexity that created vulnerabilities in the first place.

Understanding the TLS 1.2 Architecture

TLS 1.2 emerged in August 2008 as a significant improvement over TLS 1.1. The protocol introduced stronger hash functions, flexible cipher suite negotiation, and support for authenticated encryption modes like AES-GCM (Advanced Encryption Standard - Galois/Couter Mode).

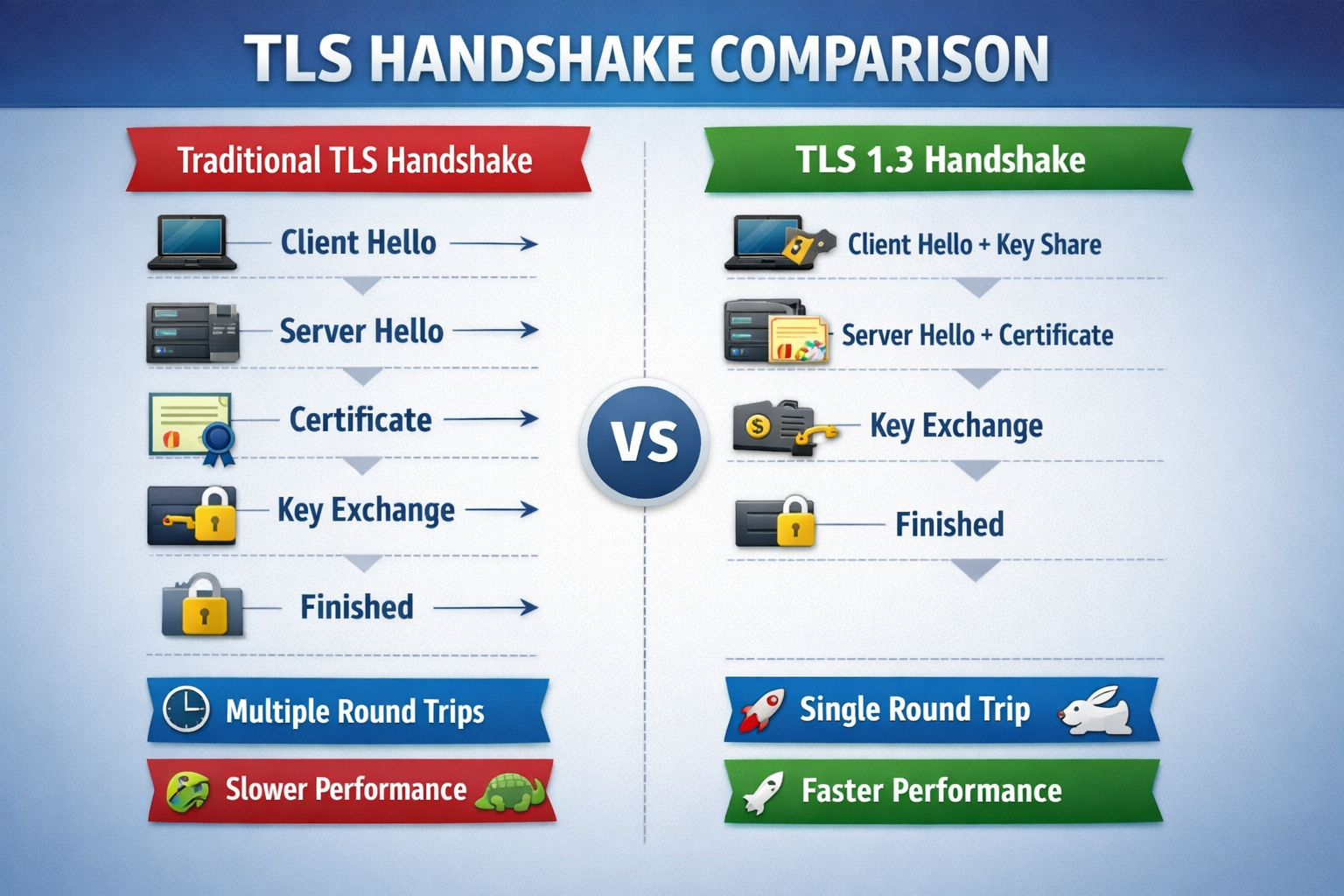

The TLS 1.2 handshake requires two full round trips between client and server before encrypted application data can flow. This 2-RTT process begins when the client sends a ClientHello message containing supported cipher suites, TLS versions, and a random value. The server responds with ServerHello, selects a cipher suite, sends its certificate, and completes key exchange.

Only after this exchange—and cryptographic verification—can both parties derive session keys and begin transmitting encrypted data. For connections spanning geographic distances, these round trips introduce measurable latency. On a connection with 100ms round-trip time, the handshake alone adds 200ms before any application data moves.

TLS 1.2 supports dozens of cipher suites, creating a complex negotiation landscape. Clients and servers must agree on key exchange methods (RSA, DH, ECDH), authentication mechanisms (RSA, ECDSA), bulk encryption algorithms (AES, 3DES, ChaCha20), and message authentication codes (SHA-256, SHA-384). This flexibility served backward compatibility but introduced risk—organizations could unknowingly configure weak cipher suites.

Perfect Forward Secrecy was optional in TLS 1.2. PFS ensures that compromising a server’s long-term private key cannot decrypt past session traffic. But static RSA key exchange—which doesn’t provide PFS—remained widely used because it was simpler to implement.

TLS 1.3: A Security-First Redesign

TLS 1.3 development focused on two objectives: reduce latency and eliminate entire classes of vulnerabilities. The protocol removes features rather than adding complexity, a counterintuitive but powerful approach to security.

The most visible change is handshake optimization. TLS 1.3 completes the handshake in a single round trip—cutting connection establishment time in half. The client sends its ClientHello along with cryptographic key shares for its preferred key exchange algorithms, essentially guessing what the server will select. When the server receives this message, it can immediately respond with ServerHello, its key share, certificate, and confirmation—all in one round trip.

Here’s how the round-trip reduction works in practice:

Client Server

| |

|----------- ClientHello + Key Share ------------->|

| |

|<---------- ServerHello + Key Share --------------|

|<-------------- Certificate ---------------------|

|<------------- Finished -------------------------|

| |

|------------- Finished ------------------------->|

| |

|<========== Encrypted Application Data ==========>|Compare this to TLS 1.2, which requires an additional round trip to complete key exchange before encrypted data can flow. In cloud environments where services communicate across availability zones or regions, this latency reduction compounds across thousands of connections per second.

TLS 1.3 also introduces 0-RTT mode for session resumption. When a client reconnects to a server it recently communicated with, it can send encrypted application data in its first message—zero round trips. This eliminates handshake latency entirely for repeat visitors, though it comes with important replay attack considerations that we’ll explore.

Cipher Suite Simplification and Security Hardening

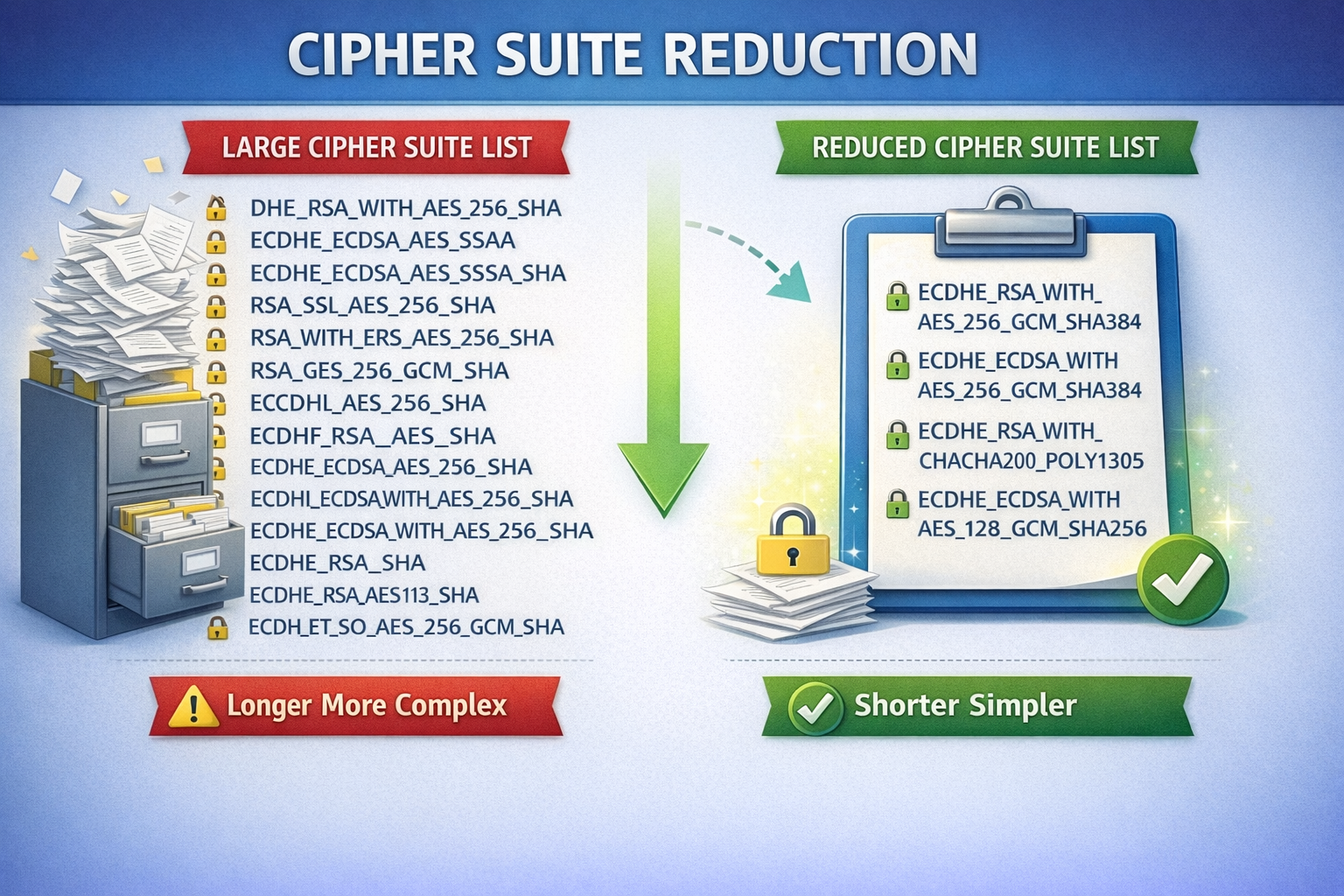

TLS 1.2 supports over three dozen cipher suites, many containing algorithms with known weaknesses. TLS 1.3 reduces this to five carefully vetted cipher suites—all using Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data.

The five TLS 1.3 cipher suites are:

- TLS_AES_256_GCM_SHA384: Uses 256-bit with Galois/Counter Mode and SHA-384 hashing for high security

- TLS_CHACHA20_POLY1305_SHA256: Combines the fast Chacha20 stream cipher with Poly1305 MAC and SHA-256 for excellent performance.

- TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256: Uses 128-bit AES with GCM and SHA-256 hashing, offering strong, common security.

- TLS_AES_128_CCM_8_SHA256: a more lightweight AES-CCM variant with an 8-byte tag, also for resource-constrained environments.

- TLS_AES_128_CCM_SHA256: Uses 128-bit AES in CCM mode with SHA-256, designed for constrained devices.

Every TLS 1.3 cipher suite uses AEAD encryption, which provides confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity in a single cryptographic operation. This eliminates vulnerabilities like padding oracle attacks that plagued CBC-mode ciphers in earlier TLS versions.

TLS 1.3 eliminates algorithms and features known to be problematic:

- Static RSA and DH key exchange (no forward secrecy)

- SHA-1 and MD5 hashing algorithms (collision attacks)

- RC4 stream cipher (multiple vulnerabilities)

- CBC-mode block ciphers (padding oracle attacks)

- Compression (CRIME attack vector)

- Renegotiation (timing attack surface)

- Custom DH groups (implementation vulnerabilities)

Perfect Forward Secrecy is mandatory. Every connection uses ephemeral Diffie-Hellman key exchange, generating unique session keys that cannot be recovered even if an attacker later compromises the server’s private certificate key. For organizations handling sensitive data, this guarantee is transformative.

The protocol also encrypts more of the handshake itself. In TLS 1.2, the server’s certificate and many handshake parameters traveled in cleartext, exposing metadata about which domains were being accessed. TLS 1.3 encrypts everything after the ServerHello message, protecting privacy and reducing the information available to network observers.

Performance Improvements That Matter

Latency matters in user experience and business outcomes. Studies consistently show that even small delays impact conversion rates, customer satisfaction, and engagement metrics. TLS 1.3’s performance improvements translate directly to measurable business value.

The single round-trip handshake reduces connection establishment time by approximately 50%. On a connection with 50ms round-trip time, this saves 50ms per new connection. For a web application serving thousands of requests per second, these milliseconds compound into significant performance gains.

Mobile networks amplify these benefits. Cellular connections often have higher latency—100ms to 300ms round-trip times are common. Eliminating a full round trip from the handshake makes encrypted connections noticeably faster on mobile devices, improving the mobile user experience without sacrificing security.

0-RTT session resumption goes further. When a client has previously connected to a server and received a session ticket, it can resume the session by sending encrypted application data in its first message. The server validates the ticket and immediately processes the request—zero round trips.

For frequently accessed services, 0-RTT can eliminate handshake latency entirely. Consider a mobile app that makes API calls throughout a user session. The first connection after the app opens completes a full 1-RTT handshake. Every subsequent connection within the session resumption window can use 0-RTT, making follow-on requests as fast as if the connection were already established.

However, 0-RTT introduces a security consideration: replay attacks. Since the client sends encrypted data before the server responds, an attacker could capture and replay the request. The protocol provides no cryptographic protection against replays for 0-RTT data.

This limitation requires careful application design. 0-RTT should only be used for idempotent operations—requests that can be safely repeated without harmful side effects. HTTP GET requests for public content work well. POST requests that modify server state do not. Organizations must evaluate whether their applications can safely use 0-RTT or should disable the feature.

The cipher suite simplification also improves performance. Fewer negotiation options mean faster cipher suite selection. AEAD encryption is computationally efficient, especially with hardware acceleration available in modern processors. These optimizations reduce CPU overhead for encrypted connections, allowing servers to handle higher throughput with the same hardware.

Security Enhancements Beyond Cryptographic Strength

TLS 1.3 doesn’t just use stronger algorithms, it fundamentally reduces attack surface by removing features that enabled past vulnerabilities.

Version rollback attacks exploited the negotiation process in earlier TLS versions. An attacker could manipulate the handshake to force both parties to use older, weaker protocol versions. TLS 1.3 changes how version negotiation works, making these downgrade attacks cryptographically impossible. The protocol includes the negotiated version in the key derivation process, so any tampering with version selection causes the handshake to fail.

The protocol removes renegotiation entirely. In TLS 1.2, client and server could renegotiate security parameters mid-connection, a feature that introduced timing-based vulnerabilities and DoS attack vectors. TLS 1.3 eliminates this capability, simplifying the protocol state machine and removing an entire class of potential exploits.

Key separation is improved through HKDF-based key derivation. Different parts of the connection use cryptographically independent keys derived from the initial shared secret. Handshake encryption keys differ from application data keys. This separation means that compromising one key doesn’t automatically compromise others.

TLS 1.3 provides stronger guarantees about what is encrypted and when. More of the handshake happens under encryption, protecting metadata about certificate contents and negotiated parameters. Even network observers with decryption capabilities for application data cannot see details about the certificate chain or extensions negotiated during the handshake.

The standardized protocol also improves implementation security. With fewer options and a simpler state machine, implementations are less likely to contain subtle bugs that could create vulnerabilities. The OpenSSL security vulnerabilities that plagued TLS 1.2 implementations—Heartbleed, FREAK, Logjam—often stemmed from complexity in optional features or rarely-used code paths. TLS 1.3’s simpler design reduces this risk.

Enterprise Migration Strategy

Moving from TLS 1.2 to TLS 1.3 requires planning, but the migration path is clearer than past protocol upgrades. Most modern servers and clients already support TLS 1.3, and the protocol was designed to coexist with TLS 1.2 during transition periods.

Begin with discovery. Inventory all systems that terminate TLS connections: load balancers, reverse proxies, API gateways, application servers, CDN configurations, and internal services. Identify which systems already support TLS 1.3 and which require updates.

Test compatibility before making changes. Modern web browsers support TLS 1.3, but some enterprise software, legacy clients, or IoT devices may not. Run compatibility tests against representative client populations to understand the impact of requiring TLS 1.3.

The migration roadmap typically follows these phases:

Phase 1: Assessment (2-4 weeks)

→ Inventory TLS termination points

→ Identify client compatibility requirements

→ Review compliance mandates and timelines

→ Audit cipher suite configurations

Phase 2: Testing (3-6 weeks)

→ Update test environments to TLS 1.3

→ Run compatibility tests with client base

→ Validate performance improvements

→ Test monitoring and logging systems

Phase 3: Pilot Deployment (4-8 weeks)

→ Enable TLS 1.3 on non-critical services

→ Monitor error rates and connection metrics

→ Gather performance data

→ Refine rollout procedures

Phase 4: Full Migration (8-12 weeks)

→ Roll out TLS 1.3 across production

→ Maintain TLS 1.2 for compatibility

→ Monitor cipher suite usage patterns

→ Plan eventual TLS 1.2 deprecation

Phase 5: Monitoring (Ongoing)

→ Track TLS version adoption rates

→ Monitor for deprecated cipher usage

→ Prepare for TLS 1.2 sunsetEnable TLS 1.3 alongside TLS 1.2 initially. Configure servers to prefer TLS 1.3 but fall back to TLS 1.2 for clients that don’t support the newer version. This approach maximizes security for modern clients while maintaining backward compatibility.

Monitor TLS version usage through connection logs. Track what percentage of connections use TLS 1.3 versus TLS 1.2. As adoption increases and legacy clients are phased out, organizations can plan to eventually require TLS 1.3 and disable TLS 1.2 entirely.

Cloud-Native Deployment Patterns

Cloud environments introduce unique considerations for TLS deployment. Services communicate across availability zones, through service meshes, behind API gateways, and in containerized environments where traditional network perimeters don’t exist.

Service mesh architectures like Istio and Linkerd automatically handle TLS for service-to-service communication. Configuring these meshes to use TLS 1.3 improves both security and performance for microservices. The mesh sidecar proxies handle certificate management, rotation, and termination—abstracting TLS complexity from application developers.

In service mesh deployments, mutual TLS becomes standard. Every service authenticates to every other service using X.509 certificates, creating zero-trust networking within the cluster. TLS 1.3 enhances mTLS by reducing handshake overhead, making the performance penalty of pervasive encryption more acceptable.

API gateways should prefer TLS 1.3 for both client-facing and backend connections. The gateway terminates TLS from external clients and establishes separate TLS connections to backend services. Using TLS 1.3 in both directions reduces latency and strengthens security guarantees across the entire request path.

Kubernetes ingress controllers support TLS 1.3 configuration through annotations or ConfigMaps. Organizations should configure ingress to advertise TLS 1.3 support and use appropriate cipher suites. For workloads requiring compliance with specific standards, ingress configuration should enforce cipher suite requirements.

Serverless functions present unique TLS considerations. Functions are ephemeral, starting and stopping based on demand. The TLS connections they establish should use 1-RTT or 0-RTT capabilities to minimize cold start latency. Cloud providers handle TLS termination at the edge, but functions making outbound API calls benefit from TLS 1.3’s performance optimizations.

Container orchestration platforms can enforce TLS policies through admission controllers. Organizations can require that all exposed services support TLS 1.3, rejecting deployments that use older configurations. This policy-as-code approach prevents configuration drift and maintains security standards.

Compliance and Regulatory Requirements

Regulatory bodies and standards organizations increasingly mandate TLS 1.3 support or deprecate older protocol versions. Understanding compliance timelines is critical for planning upgrades.

NIST Special Publication 800-52 Revision 2 provides guidance for TLS in federal information systems. The publication requires TLS 1.2 as a minimum and mandates support for TLS 1.3 beginning January 1, 2024. Federal systems must be configured to prefer TLS 1.3 when both parties support it.

The National Security Agency released guidance on eliminating obsolete TLS configurations. The guidance strongly recommends TLS 1.3 and warns that TLS 1.2 should only be used with carefully selected cipher suites that provide forward secrecy and avoid known vulnerabilities.

PCI DSS requires strong cryptography for protecting cardholder data. While the standard doesn’t explicitly mandate TLS 1.3, it requires that organizations use current security patches and eliminate weak cipher suites. Configuring TLS 1.3 aligns with PCI DSS principles by using modern, well-vetted cryptography.

Industry-specific regulations increasingly reference TLS requirements. Healthcare organizations subject to HIPAA must encrypt data in transit using appropriate protocols. Financial services regulators expect institutions to use current cryptographic standards. Government contractors must meet CMMC requirements that reference NIST guidelines.

Organizations should document their TLS configuration as part of security control evidence. This documentation should include supported protocol versions, enabled cipher suites, forward secrecy capabilities, and certificate validation procedures. Auditors increasingly review TLS configuration during security assessments.

Best Practices for TLS 1.3 Deployment

Successful TLS 1.3 deployment requires attention to configuration details, monitoring, and operational practices that maintain security over time.

- Configure servers to prefer TLS 1.3 but support TLS 1.2 during transition periods

- Use only strong cipher suites even in TLS 1.2 fallback scenarios

- Disable TLS 1.0 and TLS 1.1 entirely—these versions have known vulnerabilities

- Enable HTTP Strict Transport Security headers to prevent protocol downgrade attacks

- Implement certificate pinning for high-security applications to prevent MITM attacks

- Rotate certificates before expiration using automated certificate management

- Monitor TLS version usage to track adoption rates and identify legacy clients

- Use hardware security modules for private key storage in high-security environments

- Enable OCSP stapling to improve certificate validation performance

- Configure appropriate timeout values for session resumption tickets

- Carefully evaluate 0-RTT safety before enabling for your application’s semantics

- Disable 0-RTT for non-idempotent operations that modify server state

- Implement anti-replay mechanisms if enabling 0-RTT for sensitive operations

- Use TLS 1.3 for internal service-to-service communication, not just external traffic

- Leverage service mesh capabilities for automatic mTLS in microservices architectures

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

TLS deployment mistakes can undermine security or create operational problems. These common pitfalls appear repeatedly in real-world implementations.

- Enabling weak cipher suites “for compatibility” that defeat the purpose of upgrading

- Failing to test with actual client populations before requiring TLS 1.3

- Incorrectly configuring 0-RTT for non-idempotent operations, enabling replay attacks

- Not monitoring connection logs to verify that clients successfully use TLS 1.3

- Assuming all clients support TLS 1.3 without verification, breaking legacy systems

- Misconfiguring service mesh mTLS, creating certificate validation failures

- Setting overly aggressive session timeout values that break legitimate use cases

- Failing to implement proper certificate rotation, leading to outages during renewal

- Not testing TLS configuration after updates to underlying libraries or operating systems

- Forgetting to update load balancer configurations when backend servers support TLS 1.3

Advanced Use Cases in Modern Architectures

TLS 1.3 enables security patterns that weren’t practical with earlier protocol versions. Understanding these advanced use cases helps organizations maximize the protocol’s benefits.

Mutual TLS in Microservices

Service mesh architectures increasingly use mutual TLS for service-to-service authentication. Each microservice receives a unique X.509 certificate identifying it within the cluster. When Service A calls Service B, both parties authenticate using certificates, establishing encrypted channels that verify both endpoints.

TLS 1.3’s reduced handshake overhead makes pervasive mTLS more practical. The 1-RTT handshake means less latency penalty for establishing authenticated connections between every service. In high-throughput environments processing thousands of internal requests per second, this performance improvement makes the difference between acceptable and unacceptable latency budgets.

Certificate rotation becomes critical in mTLS deployments. Service mesh control planes automate certificate issuance and rotation, typically using short-lived certificates that expire within hours or days. TLS 1.3’s session resumption helps mitigate the performance impact of frequent certificate rotation by allowing connections to be reused across rotations within the resumption window.

IoT Device Fleet Management

Internet of Things deployments face unique TLS challenges. Devices often have constrained CPU and memory, making cryptographic operations expensive. Network connectivity may be intermittent or high-latency.

TLS 1.3 addresses these constraints. The simplified cipher suites reduce code size in embedded TLS implementations. Single round-trip handshakes reduce the time devices spend in high-power states establishing connections. Session resumption allows devices to efficiently reconnect after network interruptions without repeating full handshakes.

Device identity becomes critical in IoT security. Each device should receive a unique X.509 certificate bound to its identity. TLS 1.3’s mandatory forward secrecy protects past communications even if a device is physically compromised and its certificate extracted. This guarantee is essential when devices operate in uncontrolled physical environments.

Zero Trust Architecture Integration

Zero trust security models assume breach and verify every access attempt regardless of network location. TLS 1.3 serves as a foundational component in zero trust implementations.

Identity-aware proxies use TLS to authenticate users and devices before allowing access to applications. The proxy terminates TLS connections from clients, validates certificates, checks device posture, and enforces conditional access policies. TLS 1.3’s encrypted handshake metadata provides additional privacy by hiding certificate details from network observers.

Device posture checking integrates with TLS client certificates. Organizations issue certificates to managed devices and configure access policies that require valid certificates for application access. TLS 1.3’s strong authentication combined with other zero trust controls creates layered defenses.

CI/CD Pipeline Security

Continuous integration and deployment pipelines make thousands of API calls during builds, tests, and deployments. These calls access source code repositories, artifact registries, secret managers, and deployment APIs.

TLS 1.3 secures these pipeline connections with reduced latency. The faster handshakes mean less time waiting for encrypted connections to establish during automated workflows. For pipelines running hundreds of builds per day, the cumulative time savings become meaningful.

Service accounts used by CI/CD systems should authenticate using certificates rather than static credentials. TLS 1.3 client certificate authentication provides strong identity verification while eliminating the risks associated with shared secrets and password-based authentication.

Keyword Expansion: Related Topics and Questions

Organizations researching TLS versions often explore these related topics:

- How to configure TLS 1.3 in Nginx, Apache, and cloud load balancers.

- What cipher suites to enable for optimal security and compatibility.

- Differences between TLS and SSL and why the terminology persists.

- Perfect forward secrecy explained and why it matters for long-term data protection.

- Certificate pinning implementation strategies for mobile applications.

- HSTS header configuration to enforce encrypted connections.

- OCSP stapling for improved certificate validation performance.

- Session ticket encryption keys and rotation strategies.

- Zero-RTT replay attack scenarios and mitigation techniques.

- Service mesh TLS configuration for Istio, Linkerd, and Consul.

- Debugging TLS handshake failures with OpenSSL and network analysis tools.

- Post-quantum cryptography readiness and TLS 1.3’s role in algorithm agility.

- Browser compatibility testing for TLS 1.3 across different user agents.

- Load balancer TLS offloading versus end-to-end encryption trade-offs.

- Certificate lifecycle management and automated renewal workflows.

- FIPS 140-2 compliant TLS implementations for government systems.

- Performance testing methodologies for comparing TLS versions.

- Migration from hardware security modules to cloud-based key management.

- TLS inspection and decryption at enterprise network security appliances.

- Container orchestration TLS bootstrapping and secret distribution.

External Resources

These authoritative resources provide additional technical depth and implementation guidance:

- RFC 8446: The TLS Protocol Version 1.3 - Official TLS 1.3 specification from IETF

- NIST Special Publication 800-52 Revision 2 - Guidelines for TLS implementations in federal systems

- CISA TLS Best Practices - Cybersecurity guidance for transport layer security

- Cloudflare: TLS 1.3 Explained - Technical deep-dive into protocol improvements

- OWASP Transport Layer Protection Cheat Sheet - Security configuration recommendations

Transform Your PKI Infrastructure

Modern enterprises require automated, cloud-native certificate management that scales with your infrastructure. Manual processes create security gaps, expired certificates cause outages, and compliance audits expose configuration weaknesses.

Qcecuring provides enterprise PKI solutions that automate certificate lifecycle management, enforce TLS 1.3 standards across your infrastructure, integrate with service meshes and cloud platforms, and provide visibility into your encryption posture.

Schedule a personalized demo to see how organizations are automating TLS deployment while strengthening security and meeting compliance requirements.

Final Summary

TLS 1.3 represents a fundamental improvement over TLS 1.2, delivering measurable security and performance benefits for enterprise infrastructure:

- 50% faster connection establishment through single round-trip handshakes, reducing latency for every encrypted connection

- Mandatory forward secrecy ensures compromised keys cannot decrypt past communications, protecting long-term data confidentiality

- Simplified cipher suites eliminate weak algorithms and reduce attack surface by using only AEAD encryption modes

- Enhanced privacy through encrypted handshake metadata that hides certificate details from network observers

- Enterprise migration paths enable gradual adoption while maintaining backward compatibility during transition periods

Organizations should begin planning TLS 1.3 deployment immediately, starting with compatibility testing and progressing through phased migration that minimizes disruption while maximizing security improvements.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the main difference between TLS 1.2 and TLS 1.3?

The primary difference is handshake efficiency and security architecture. TLS 1.3 completes encrypted connection establishment in one round trip versus two for TLS 1.2, reducing latency by approximately 50%. The newer protocol also mandates forward secrecy, eliminates weak cipher suites entirely, and encrypts more of the handshake metadata to protect privacy.

Is TLS 1.3 backwards compatible with TLS 1.2?

Yes, TLS 1.3 was designed for backward compatibility. Servers can support both protocols simultaneously, preferring TLS 1.3 for clients that support it while falling back to TLS 1.2 for legacy clients. This allows gradual migration without breaking existing connections. The protocol includes downgrade protections that prevent attackers from forcing connections to use older versions.

Should I disable TLS 1.2 entirely and require TLS 1.3?

Not immediately. While TLS 1.3 is superior, some clients and devices don’t yet support it. Begin by enabling TLS 1.3 alongside TLS 1.2, monitoring adoption rates through connection logs. Once your client base demonstrates strong TLS 1.3 support and legacy systems are updated, you can plan to deprecate TLS 1.2. Federal systems must support TLS 1.3 as of January 2024 per NIST guidance.

What are the security risks of 0-RTT in TLS 1.3?

Zero round-trip time mode allows clients to send encrypted data in their first message, eliminating handshake latency for session resumption. However, the protocol cannot protect against replay attacks for this initial data. An attacker could capture and replay the first message, causing the server to process it multiple times. Only use 0-RTT for idempotent operations like HTTP GET requests, never for state-changing operations.

Which cipher suites should I enable in TLS 1.3?

TLS 1.3 only defines five cipher suites, all using AEAD encryption. For most deployments, enable TLS_AES_256_GCM_SHA384 and TLS_CHACHA20_POLY1305_SHA256 as your preferred options. These provide strong security with good performance. The AES suites work best when hardware acceleration is available, while ChaCha20-Poly1305 performs better on devices without AES hardware support like many mobile processors.

How does TLS 1.3 improve performance for mobile applications?

Mobile networks typically have higher latency than wired connections, often 100-300ms round-trip time. Reducing the handshake from two round trips to one saves 100-300ms on every new connection. Session resumption with 0-RTT can eliminate handshake latency entirely for subsequent connections. For mobile apps making frequent API calls, these improvements create noticeably faster response times.

Can I use TLS 1.3 with mutual TLS authentication?

Yes, TLS 1.3 fully supports mutual TLS where both client and server authenticate using X.509 certificates. In fact, TLS 1.3 makes mTLS more practical by reducing the handshake overhead. Service mesh architectures commonly use TLS 1.3 with mTLS for service-to-service authentication, benefiting from both the security guarantees and performance improvements.

What’s the difference between TLS and SSL?

SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) is the predecessor to TLS (Transport Layer Security). SSL 3.0 was deprecated due to security vulnerabilities, replaced by TLS 1.0 in 1999. The names are often used interchangeably due to historical reasons, but modern encrypted connections exclusively use TLS. When people refer to “SSL certificates,” they actually mean X.509 certificates used with TLS protocols.

How do I test if my server properly supports TLS 1.3?

Use OpenSSL command-line tools to test TLS 1.3 support: openssl s_client -connect yourserver.com:443 -tls1_3. Online tools like SSL Labs’ Server Test provide comprehensive analysis of your TLS configuration, including supported protocols, cipher suites, and potential vulnerabilities. Monitor your server logs to track what percentage of connections successfully negotiate TLS 1.3.

What compliance standards mandate TLS 1.3?

NIST SP 800-52 Revision 2 requires federal systems to support TLS 1.3 as of January 2024. While PCI DSS doesn’t explicitly mandate TLS 1.3, it requires current security patches and elimination of weak cryptography, which aligns with TLS 1.3 adoption. Many industry-specific regulations reference NIST guidelines or require “current cryptographic standards,” making TLS 1.3 support increasingly expected for compliance.

Ready to Secure Your Enterprise?

Discover how QCecuring can help you automate certificate lifecycle management, secure SSH keys, and protect your cryptographic infrastructure.