A detailed exploration of RC4 encryption, covering algorithm mechanics, weaknesses, real-world attacks, cryptanalysis, enterprise risks, and why organizations must migrate to stronger encryption standards.

Introduction

RC4 (Rivest Cipher 4), also known as ARC4 or Arcfour, is a symmetric stream cipher that once dominated the world of practical encryption. For many years it was the “go-to” choice for developers because it was easy to implement, extremely fast, and efficient even on low-power or embedded devices. It ended up everywhere: in SSL/TLS, early HTTPS, WEP Wi‑Fi security, Microsoft Office encryption, and various custom protocols.

Over time, however, cryptographers started to uncover deep structural weaknesses in RC4. What initially looked like a simple and elegant cipher turned out to have serious biases and flaws that attackers could exploit in real-world scenarios. Today, RC4 is considered insecure and has been deprecated across modern standards and platforms. This article walks through how RC4 works internally, why its design leads to vulnerabilities, and what safer modern alternatives you should be using instead.

By the end of this deep dive, you will understand how RC4 generates its keystream, what attacks like FMS, Bar‑Mitzvah, and the Royal Holloway work actually do in practice, how continued RC4 usage can impact compliance and risk posture, and how to start migrating toward more robust ciphers such as AES and ChaCha20.

What is RC4 Encryption?

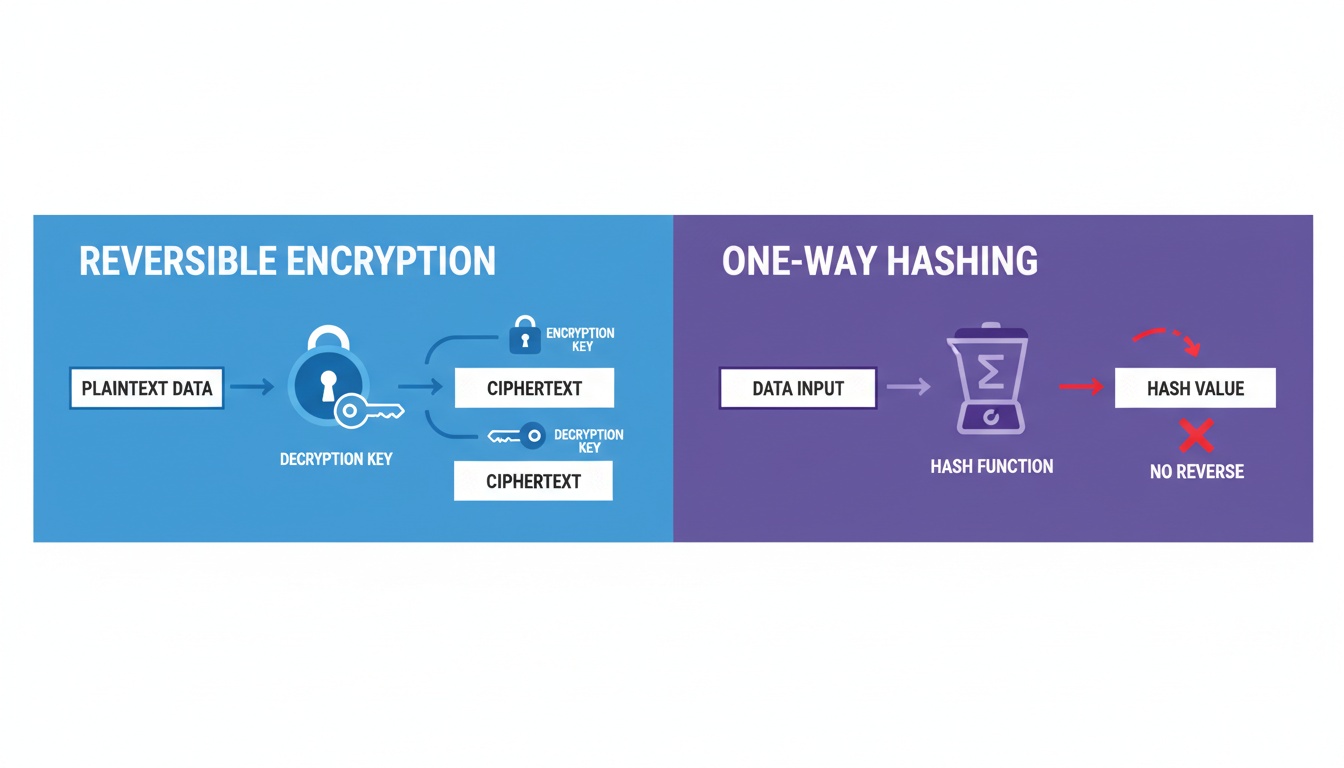

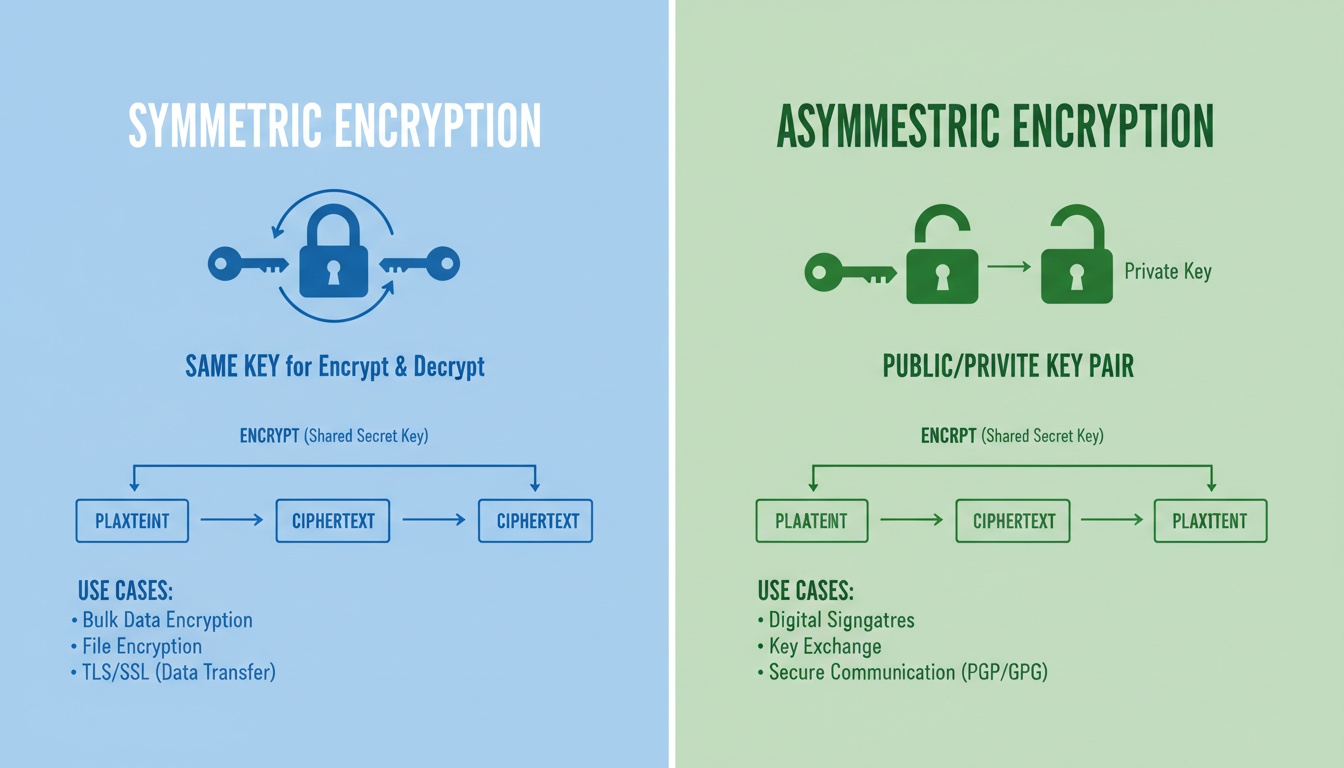

RC4 is a symmetric key stream cipher, which means the same secret key is used to both encrypt and decrypt data. Instead of encrypting data in fixed-size blocks (like AES does), RC4 produces a continuous pseudorandom keystream and encrypts data one byte at a time. Each plaintext byte is combined with one keystream byte through an XOR (exclusive OR) operation to produce ciphertext.

Because encryption and decryption both rely on XOR with the same keystream, the process is reversible: applying the same keystream to the ciphertext recovers the original plaintext. This simplicity made RC4 highly attractive in early network protocols and software products. However, the quality and predictability of that keystream are exactly what determine how secure the cipher really is, and that is where RC4 ultimately fails.

Key Properties of RC4 Cipher

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Cipher Type | Stream cipher |

| Key Size | 40–2048 bits (128-bit commonly used in practice) |

| Encryption Speed | Very fast and lightweight |

| Security Status | Deprecated / Insecure in modern cryptographic standards |

| Use Cases | Historically used in WEP, WPA, SSL/TLS, Microsoft Office, etc |

How Does RC4 Work? (Step-by-Step)

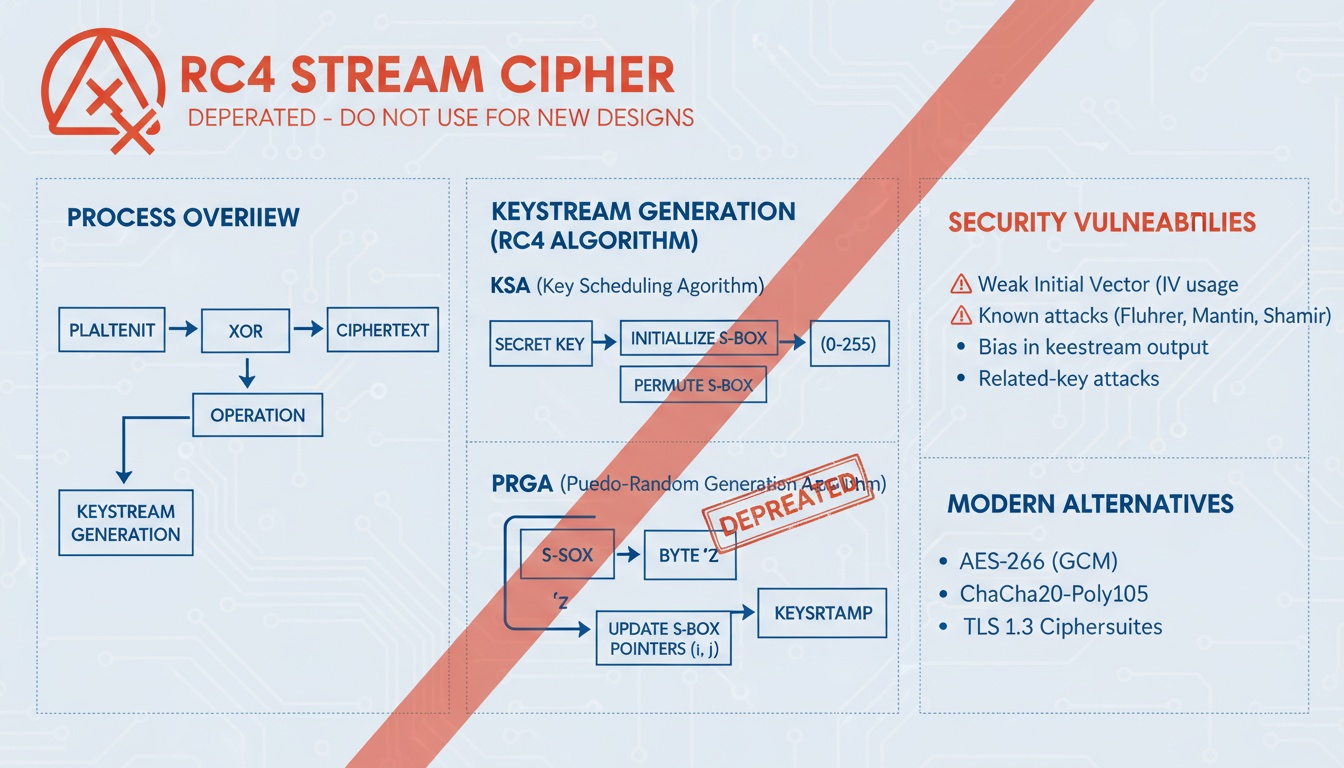

Internally, RC4 relies on two main components that work together to generate the keystream:

- Key Scheduling Algorithm (KSA)

- Pseudo-Random Generation Algorithm (PRGA)

The KSA takes the secret key and builds an initial internal state. The PRGA then uses that state to output one keystream byte at a time. Each keystream byte is XORed with one plaintext byte, resulting in the ciphertext for that position.

1. Key Scheduling Algorithm (KSA)

The KSA starts by initializing a 256-byte array called S, often referred to as the S‑Box or state array. Initially, S is filled with the values 0 through 255 in order:

S = 0, S = 1, …, S = 255

text

The algorithm then mixes this array based on the provided key. It cycles through all 256 positions of S, using key bytes and modular arithmetic to compute an index j and swap elements of the array. After this process, S becomes a key-dependent permutation of the numbers 0–255.

In theory, this shuffled array should behave like a random permutation. In practice, however, the way KSA performs these swaps leads to patterns and biases in the initial part of the keystream, which attackers can exploit if they can observe enough encrypted data.

2. Pseudo-Random Generation Algorithm (PRGA)

Once the KSA has finished, the PRGA takes over to produce the actual keystream. It maintains two index variables (usually called i and j) that move through the S array, performing swaps and outputting bytes. For each byte of data to be encrypted or decrypted, PRGA:

- Updates the indices i and j.

- Swaps two positions in S.

- Uses the updated S to choose a keystream byte.

- XORs that keystream byte with the corresponding plaintext or ciphertext byte.

This process repeats for as long as there is data to process. Because the PRGA is so simple and operates on a small array, RC4 can generate keystream bytes at very high speed, which was ideal for early network hardware and constrained devices.

RC4 Encryption Flow Diagram

Conceptually, the encryption and decryption flow look like this:

Plaintext + Keystream -> XOR -> Ciphertext Ciphertext + Keystream -> XOR -> Plaintext

text

As long as the keystream is unpredictable and never reused with the same key and nonce combination, this model can be secure. Unfortunately, RC4 does not meet those requirements reliably.

Internal RC4 Algorithm Representation (Simplified Pseudocode)

The following pseudocode captures the structure of RC4 in a simplified Python-style format. It illustrates both the KSA (initialization and key mixing) and the PRGA (keystream generation and XOR):

Key Scheduling Algorithm (KSA) S = [0..255] j = 0 for i in 0..255: j = (j + S[i] + key[i % key_length]) % 256 swap(S[i], S[j])

Pseudo-Random Generation Algorithm (PRGA) i = j = 0 while data exists: i = (i + 1) % 256 j = (j + S[i]) % 256 swap(S[i], S[j]) K = S[(S[i] + S[j]) % 256] output_byte = plaintext_byte XOR K

text

Although this looks straightforward and elegant, the interactions between KSA and PRGA are where subtle statistical weaknesses appear. These weaknesses are not obvious from the code but become clear when you analyze many keystreams.

Strengths of RC4 (Why It Was So Popular)

Despite its current reputation, RC4 rose to prominence for good reasons. For many years, it solved real problems in networking and software.

Key advantages included:

- Very fast: RC4 requires only simple operations (additions, swaps, XORs), making it extremely efficient in both software and hardware.

- Lightweight: It uses a small amount of memory, which made it suitable for routers, embedded systems, and early mobile devices.

- Easy to implement: The algorithm fits in a short snippet of code and does not require complex math or large lookup tables.

- Good for early SSL/TLS: In the early days of HTTPS, RC4 provided better performance than many alternatives and helped make secure web connections practical.

These properties led to widespread adoption, and RC4 became deeply embedded in various protocols and products before its weaknesses were fully understood.

Why RC4 Is Weak: Core Cryptographic Flaws

Over time, researchers discovered that RC4’s internal design leads to non-random behavior in the keystream. Instead of behaving like a truly random sequence, the keystream exhibits statistical biases, especially in the initial bytes. When an attacker can collect enough ciphertexts, those biases can leak information about the plaintext or even about the encryption key.

Some of the main weaknesses include:

| RC4 Vulnerability | Description |

|---|---|

| Key Scheduling Bias | Certain key patterns influence the initial state in a predictable way |

| Weak initial keystream | The first several hundred bytes contain noticeable statistical biases |

| No built-in authentication | RC4 alone does not provide integrity or authenticity |

| Prone to key recovery | Given enough traffic, attackers can recover parts of the key or plaintext |

A key lesson from RC4 is that a fast and simple cipher is not enough; the keystream must also be indistinguishable from random, and RC4 fails that requirement in multiple ways.

Major Real-World RC4 Attacks

Theoretical weaknesses turned into practical attacks as researchers developed methods to exploit RC4 in real protocols and products. Some of the most influential attacks are:

1. FMS Attack (Fluhrer–Mantin–Shamir)

- One of the earliest and most famous attacks on RC4.

- Targets WEP (Wired Equivalent Privacy), which used RC4 with weak initialization vectors (IVs).

- By capturing a large number of WEP packets and analyzing patterns in the keystream, attackers can recover the Wi‑Fi key and decrypt traffic.

This attack was a key reason why WEP was declared insecure and replaced by WPA/WPA2.

2. Bar-Mitzvah Attack (2015)

- Exploits long-known statistical biases in the RC4 keystream, especially in the first part of the stream.

- Can recover portions of plaintext (such as cookies or session tokens) without fully recovering the key.

- Demonstrated that RC4 in SSL/TLS was vulnerable in practice, not just in theory.

The Bar‑Mitzvah results accelerated the move away from RC4 in mainstream HTTPS deployments.

3. Royal Holloway Attack

- A family of attacks developed by researchers at Royal Holloway, University of London, targeting RC4 in TLS.

- Requires capturing a very large number of TLS sessions (often millions), then using keystream biases to extract sensitive data like authentication cookies.

- Showed that even when RC4 was used in a modern protocol like TLS, it could still be exploited at scale with sufficient data and computing power.

These attacks collectively convinced standards bodies and browser vendors that RC4 had to be phased out.

Business and Security Risks of Using RC4

Continuing to use RC4 today is not just a technical risk; it is also a business, compliance, and reputational risk. Organizations that still rely on RC4 in legacy systems face several concrete issues:

| Risk | Impact |

|---|---|

| Data Exposure | Sensitive communications may be decrypted by attackers over time |

| Compliance Violations | Use of deprecated ciphers can violate PCI-DSS, HIPAA, NIST guidelines |

| TLS Handshake Failure | Modern browsers and clients may refuse connections using RC4 |

| Regulatory Penalties | Failed audits and non-compliance can lead to fines or sanctions |

| Loss of Trust | Breaches erode customer confidence and damage brand reputation |

Modern browsers such as Chrome, Firefox, and Edge have fully removed support for RC4, meaning that any public-facing service attempting to use RC4 will either fail to negotiate secure connections or be forced into unsafe configurations.

RC4 in Cyber Security Today: Deprecated & Unsupported

RC4 is now treated as an obsolete cipher across most reputable standards and platforms. If you still see RC4 in any configuration, consider it a red flag that requires immediate attention.

| Platform | RC4 Support Status |

|---|---|

| TLS 1.3 | Not supported at all |

| PCI-DSS | Explicitly disallowed for cardholder data |

| Microsoft | Removed from recent Windows Server defaults |

| Wi‑Fi (WEP) | Deprecated and replaced by WPA/WPA2/WPA3 |

| TLS 1.0 / 1.1 | Deprecated, may exist only in legacy stacks |

In other words, RC4 persists mainly in older or poorly maintained systems. Modern cryptographic hygiene requires phasing it out entirely.

RC4 vs AES vs ChaCha20: Which Is Better?

When evaluating encryption options today, RC4 should not be considered a viable choice. Instead, AES and ChaCha20 are the standard recommendations for most environments.

| Feature | RC4 | AES | ChaCha20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cipher Type | Stream | Block cipher | Stream cipher |

| Security | Weak | Strong (industry standard) | Strong, modern design |

| Speed on Mobile | Fast | Medium (hardware helps) | Very fast, especially in software |

| Vulnerability | High | Very low (when used in secure modes) | Very low |

| Modern Use | Deprecated | Recommended widely | Recommended, especially in TLS and VPNs |

AES, especially in modes like GCM, is the default choice in most enterprise systems and cloud platforms. ChaCha20, combined with Poly1305 for authentication, is widely used in protocols like modern TLS where performance and security are both critical.

How to Disable RC4 in Servers

If you discover that your servers still support RC4, you should disable it as soon as possible. The exact steps depend on your platform and software stack, but here are a couple of common examples.

Windows Registry to Disable RC4 Cipher

On Windows Server systems that still expose legacy cipher configurations, RC4 can often be disabled via the registry:

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\SecurityProviders\SCHANNEL\Ciphers\RC4 128/128] “Enabled”=dword:00000000

text

After making this change, a reboot or service restart is typically required. Always test changes in a staging environment before applying them to production.

OpenSSL Configuration

In environments using OpenSSL (for example, Apache or Nginx with OpenSSL-based TLS), you can explicitly exclude RC4 in cipher configuration strings:

!RC4:!MD5:!DES

text

This snippet removes RC4, as well as other weak primitives like MD5 and DES, from the allowed cipher suites. Consult your specific web server or reverse proxy documentation to ensure you are updating the correct configuration files.

Recommended Secure Alternatives to RC4

When replacing RC4, the goal is not just to “turn it off” but to move toward well-supported, modern, and authenticated encryption schemes. Common and recommended options include:

-

AES-256-GCM

- Provides both confidentiality and integrity in one mode.

- Widely supported in TLS, VPNs, databases, and application frameworks.

-

ChaCha20-Poly1305

- Designed for high performance in software without relying on specialized hardware.

- Used in modern TLS configurations, mobile apps, and VPN protocols.

-

AES-CCMP (Wi‑Fi WPA2/WPA3)

- Standard for secure Wi‑Fi encryption in WPA2 and WPA3.

- A direct successor to WEP’s RC4-based design.

-

ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography) for signatures and key exchange

- Not a direct replacement for RC4 (since RC4 is a symmetric cipher), but ECC is a modern choice for establishing keys and performing digital signatures in secure protocols.

By standardizing on these algorithms, organizations can align with industry best practices and compliance requirements while also reducing their attack surface.

Conclusion

RC4 played an important historical role in the evolution of cryptography and secure communications. Its simplicity, speed, and low resource usage helped make encryption more practical at a time when hardware was limited and secure protocols were still maturing. However, the same design that made RC4 attractive has been shown to contain serious cryptographic flaws that attackers can exploit in realistic scenarios.

Because of its predictable keystream, biased key scheduling, and susceptibility to well-documented attacks, RC4 is no longer suitable for protecting sensitive data. Organizations should systematically remove RC4 support from their environments, migrate to stronger algorithms like AES and ChaCha20, enforce secure TLS configurations, and regularly review legacy systems and protocols for deprecated cryptography.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is RC4 in cryptography?

RC4 is a symmetric stream cipher that encrypts data by generating a pseudorandom keystream and combining it with plaintext using XOR.

Is RC4 encryption still used?

RC4 is now considered insecure and has been deprecated in major standards and modern browsers. Any use today is generally limited to legacy or misconfigured systems.

What is RC4 decrypt?

RC4 decryption uses the same keystream generation process as encryption. Applying XOR with the same keystream to the ciphertext recovers the original plaintext.

What is RC4 key length?

RC4 supports keys from 40 up to 2048 bits, with 128-bit keys having been the most common in practice. Increasing the key length does not fix the underlying design weaknesses.

Which is better: RC4 or AES?

AES is far more secure, better analyzed, and widely recommended by modern standards bodies. RC4 should not be used in new designs and should be removed wherever it still appears.

Need help migrating from RC4 or securing enterprise cryptography?

Contact our encryption specialists

Ready to Secure Your Enterprise?

Discover how QCecuring can help you automate certificate lifecycle management, secure SSH keys, and protect your cryptographic infrastructure.